St Giles Hill Church

The first record of the church of St Giles was in 1096 when “William II granted to the bishop and to the monks of the cathedral a fair of three days at the church of St. Giles on the eastern hill of Winchester”. It was again mentioned in 1172 when Pope Alexander III confirmed the Cathedral Priory in the possession of the church of St. Giles. However, prior to this, it is possible that the church and its cemetery already existed. This is certainly so for the cemetery as there was already an important early Anglo-Saxon on the hill top.

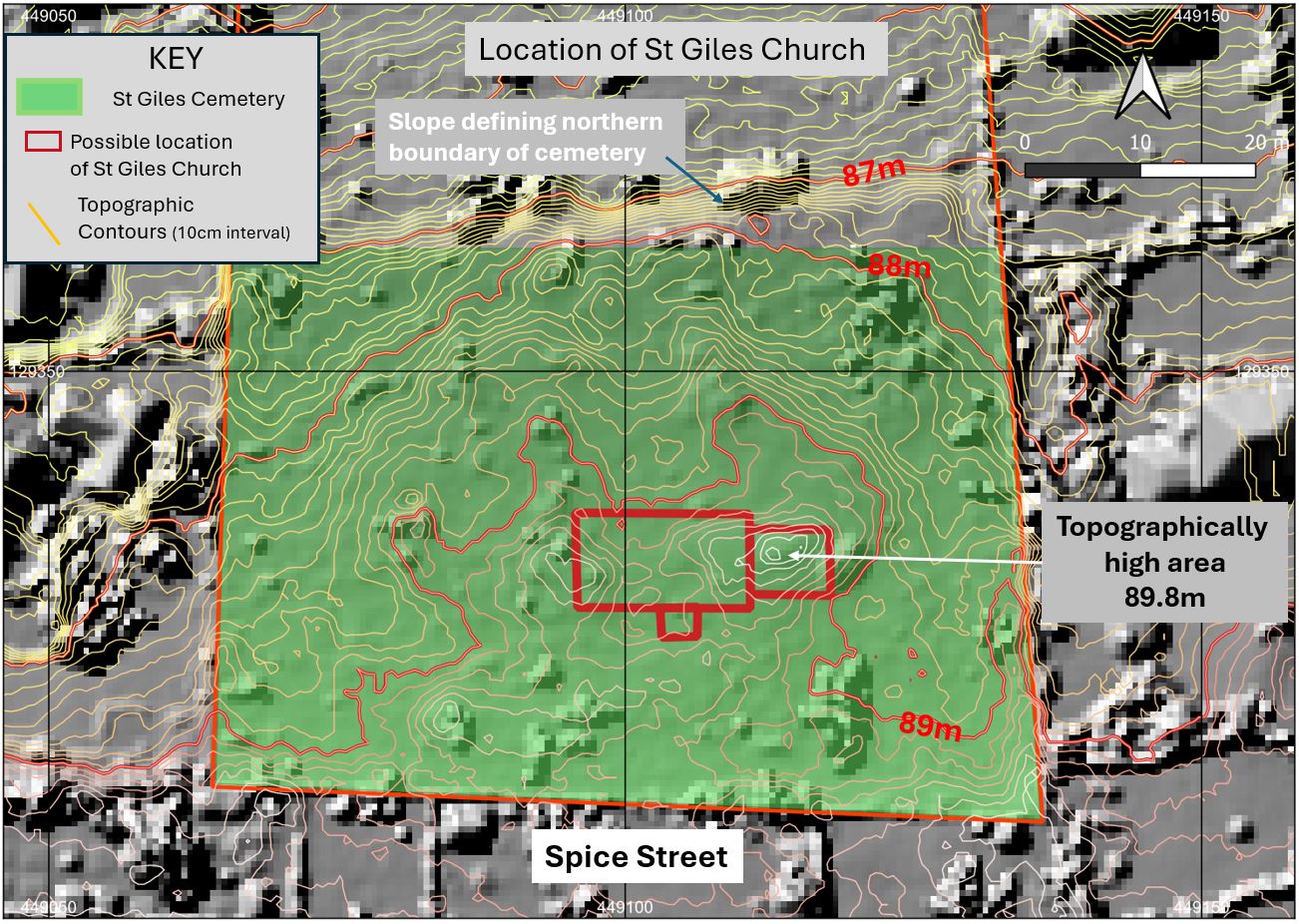

Map of St Giles Hill Graveyard

Possible site of the church

There is no record of the exact location of the church or chapel. Derek Keene puts it in the center of the plot, probably because this is a typical location in medieval churches. Today, there is a mounded area close to the center that could conceal the foundations of the church. The detailed topographic contours in the map below (created from LIDAR imagery) highlight the mound. The church outline is a scale drawing of a typical medieval church. The length of the church is about 21m.

Map of the medieval cemetery with high resolution topogeraphic contours

Photo showing the mounded area

Wrought iron railings formig an enclosure

There is a railing enclosure constructed from wrought iron about 1.5m by 4.5m in the medieval part of the graveyard. On detailed maps used by the Winchester City Council planning department, it is labeled as the "site of medieval St Giles Chapel".There is no evidence for this

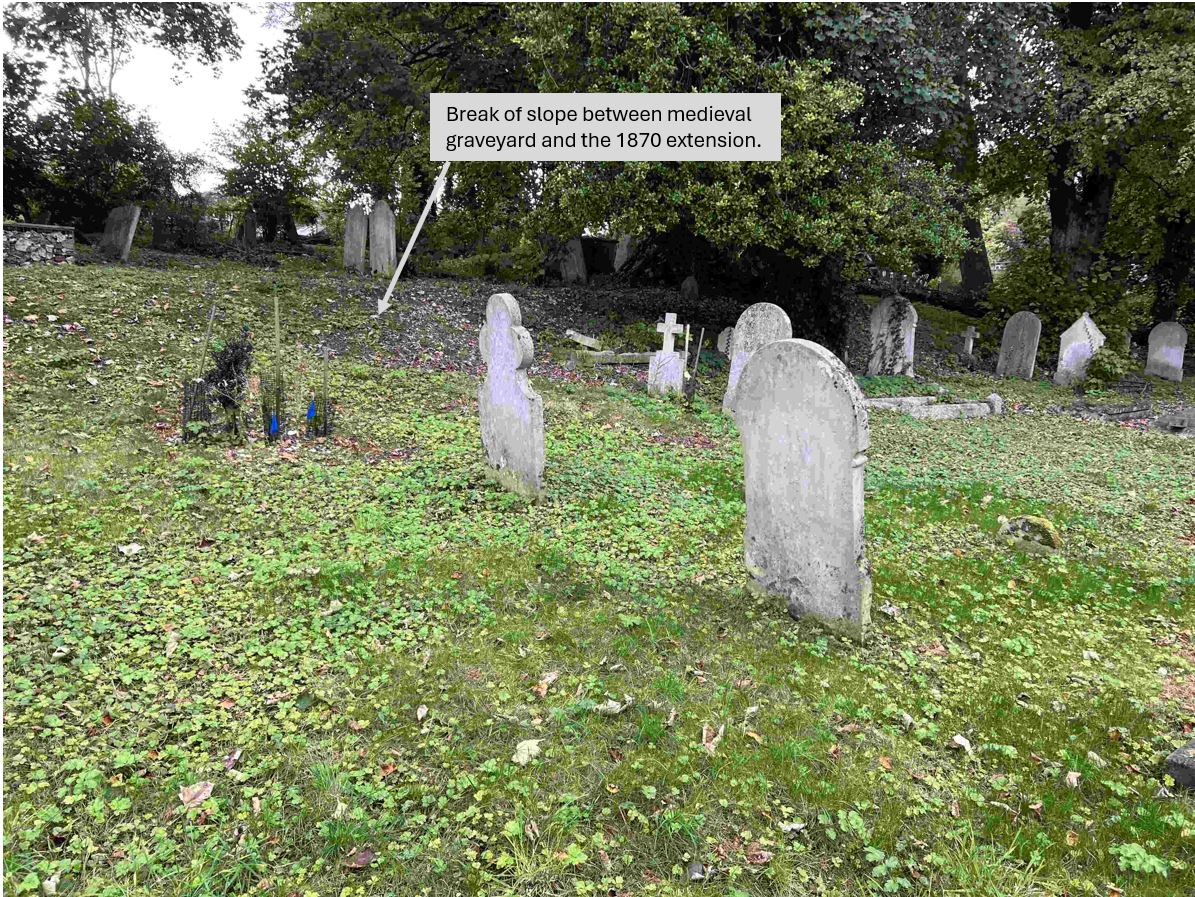

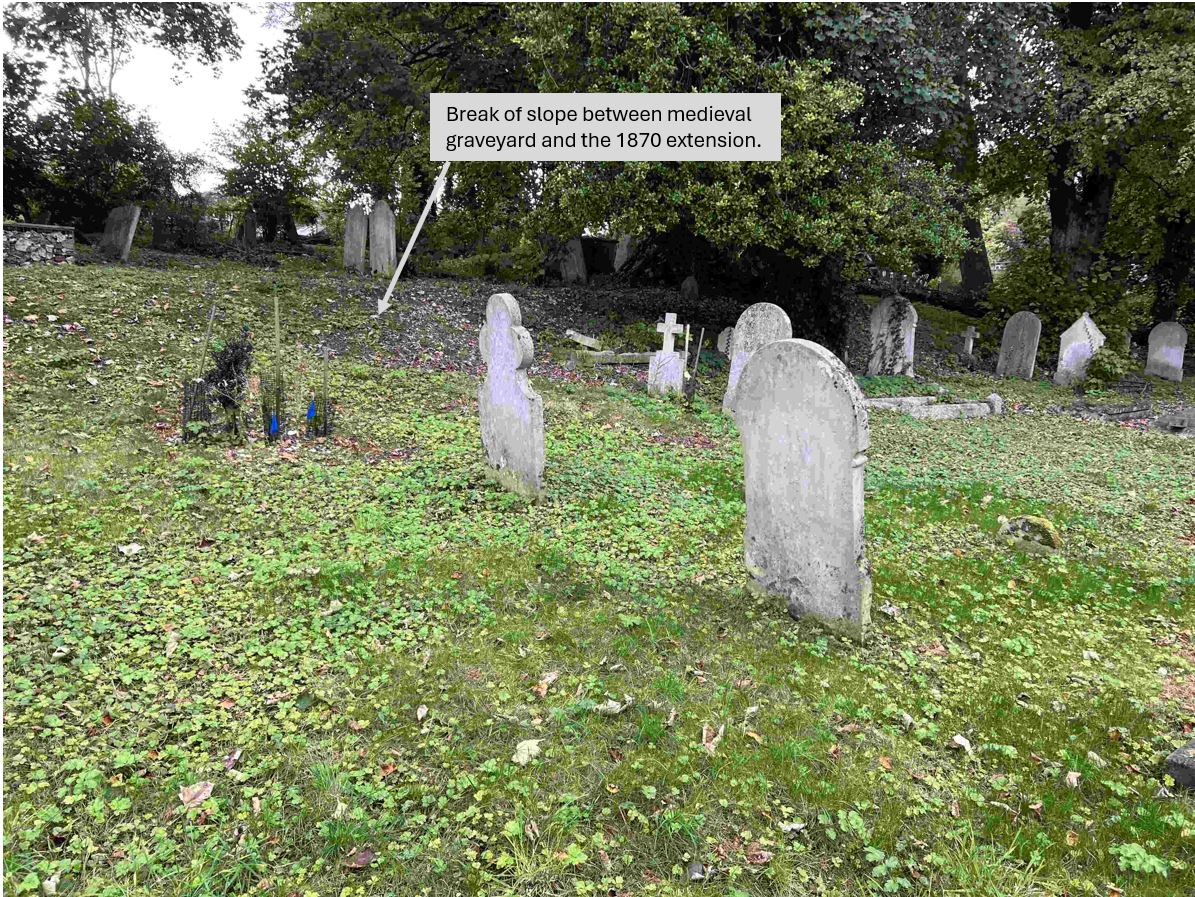

Break of slope on north boundary of medieval graveyard

The northern boundary of the medieval cemetery plot is marked by a break of slope about 1m high. This is the location of one of the old St Giles Fair street and was a road called Crok Lane (visible on the Goodson map od 1750) that existed until about 1800.

Church or chapel

Derek Keene refers to it as the parish church of St Giles in his epic publication on Winchested in the Middle Ages. He describes how various medieval texts refer to it as either church or a chapel.

Initially, the St Giles Church may have had its own parish, but by the late 13th century appears to have merged with Winnall and is recorded as being attached to the parish of Winnall (within the Bishops Winnall Estate). During this period the immediate area around the church would probably only have been populated for a short period during the fair of St Giles. Winnall was served by St Martins church which would have had a permanent congregation. In the list of churches of c. 1270, only the church of Winnall is recorded. In 1284 the church of St. Giles with the chapel of Winnall was among the Winchester churches in which the king and the Cathedral Priory gave up their interest to the bishop. Both Winnall church and St Giles Church appear to have paid pension to the priory.

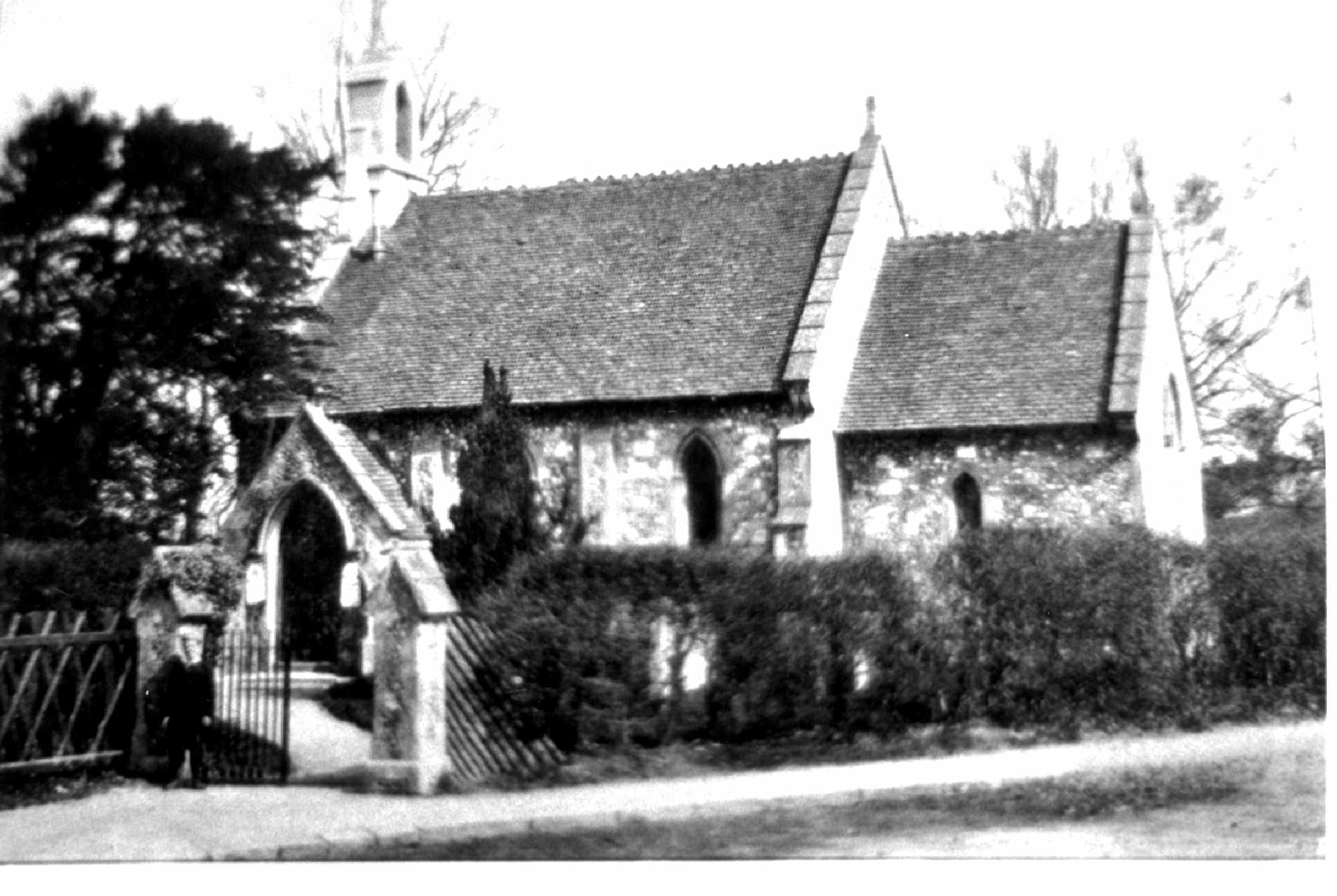

St Andrews Chilcomb

St Martins Winnall was extensively rebuilt by the victorians and so is probably not a good analogue but the basic design appears to have stayed.

Whilst there are apparent contradictions in historic documents with regard to the relative importance of the two it is clear that the St Giles Church was an important place.

The Church of St Giles played an important role in St Giles Fair. The church of St Giles would have played a major part in the affairs of the St Giles Hill Fair. Winchester Priory had the right to offerings in the church during the fair and on St. Giles’s Day and the week after. They also held custody of the keys during the same period, and the right of burial of the dead in the cemetery. In the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries the offerings at fair-time would have been of great value to St. Giles’s church.

What did the church look like

Little is known of the structure of the church. We do know that it was burnt down a few times. It was rebuilt after a serious fire at the fair in 1197 and was burnt down in 1231 and again rebuilt.

The classic layout of Saxon and Norman churches would have been a Nave with an attached chancel and a porch. A good local example is St Andrews Chilcomb. The Saxon church of Corhampton built around 1020 is another example.

Typical Saxon church plan

Plan of the medieval church at Otterbourne

Construction materials

The materials used in its construction are not known. Many churches of the Saxon and early Norman periods were built from timber.

In the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, the offerings at fair-time would have been of great value to St. Giles’s church and the cemetery was sometimes used as a location to make commercial transactions. With this wealth, there is no reason why the church could not have been built from stone.

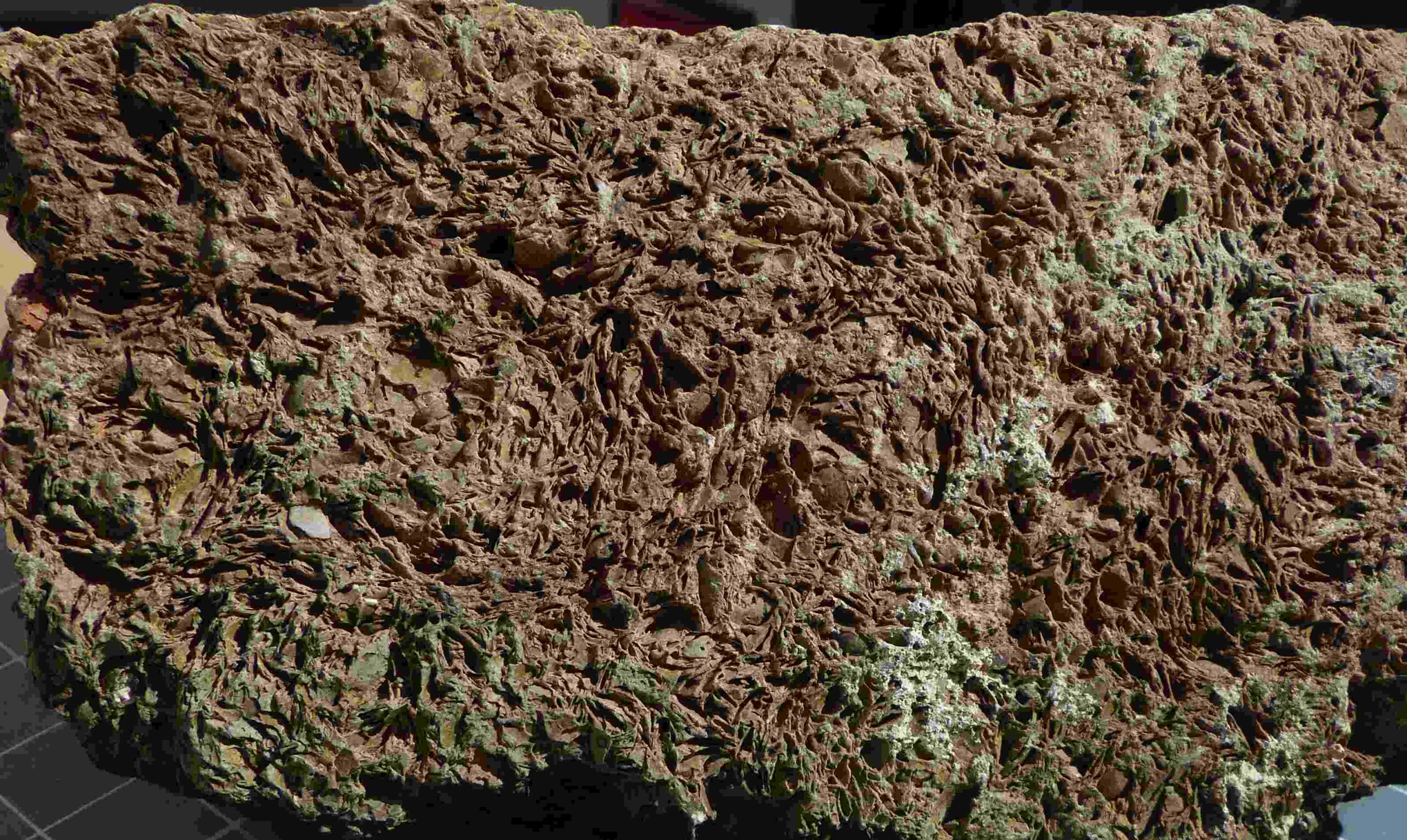

We do have evidence from building stone artifacts left on the site that suggests stone may have been used. This is in the form of several pieces and one large ashler block of Quarr stone. This is a particular and very distinctive type of stone that was used extensively by the early Normans. It was quarried on the north coast of the Isle of Wight and was used to build, Winchester Cathedral, Chichester Cathedral, Hyde Abbey and other ecclesiastical buildings. Smaller churches like St John the baptist in the soke also have it. It is significant because the quarries were exhausted by the late 12th century.

Quarr ashler block

Quarr stone block from the norman tower - Winchester Cathedral

Worked quarr stone from St Giles hill Graveyard

In the early sixteenth century records show the chapel was still being repaired. It was still standing in 1542 when John Leland the British typographer visited St Giles Hill and saw the chapel. His famous described it as "having once been a ‘far bigger thing". It was probably demolished within a few years of Leland’s visit.

Medieval artifacts found on the site

Three articles from St Giles Hill Graveyard are amongst the longest standing items in the Winchester Museum. They are 3 pricket candlesticks. They were donated by the Rev. Gunner in 1851. According to the Rev. Gunner they were found in 1850 on the site of the medieval St Giles chapel when men were excavation for a tomb. They are item No.8 in the very first museum catalogue dated 1853. They can be seen on the first floor of the city museum.

A description of the objects and photographs are shown below.

WINCM:ARCH 2245.1 Pricket candlestick. Circular base, circular pan and cylindrical shaft. Scratch on underside of pan and damaged piercing from beneath, From St Giles Hill (site of the medieval chapel).

WINCM:ARCH 2245.2 Pricket candlestick with a claw foot. Damage to the pan – crack in the side. From St Giles Hill (site of medieval chapel).

WINCM:ARCH 2245.3 Pricket candlestick. Broken top of the shaft. Three feet with giult decoration. Two globular collars on shaft and zoomorphic terminals to the legs. Wo collars on the legs. A three part decorative skirt, two now missing. The surviving part has a trefoil terminal. From St Giles Hill (site of medieval chapel).

WINCM:ARCH 2245.1 Pricket candlestick.

WINCM:ARCH 2245.2 Pricket candlestick.

Pricket candlestick. WINCM:ARCH 2245.3

Southern boundary of the medieval graveyard

The north boundary of the Medieval cemetery is marked today by a break of slope that also marks the orientation of the old Crok Lane a part of the only St Giles Fair grid of roads. It was still in existence in the late 18th C.

The map below shows the main features as shown on maps by Godson and others.

Late 18th century layout of east Winchester

the main sources of information: Please contact Dave Stewart with questions.

Dr David Stewart:- dave@stgileshill.org.uk