St Giles Hill Fair

It origins

Bishop Walkelin procured from William II (William Rufus) a grant to hold a fair for 3 days before the feast of St. Giles (September 1st) on the Eastern hill of Winchester. This was extended by Henry I for a further five days in exchange for some lands of the bishop of Winchester. King Stephen extended the grant further by six days. Henry II in the 1150's doubled the number of days allowed to sixteen. This was frequently increased to twenty or twenty-four by temporary grants and often exceeded during the 12th and much of the following century. The principal aim of the fair would have been to sell the bishop's produce.

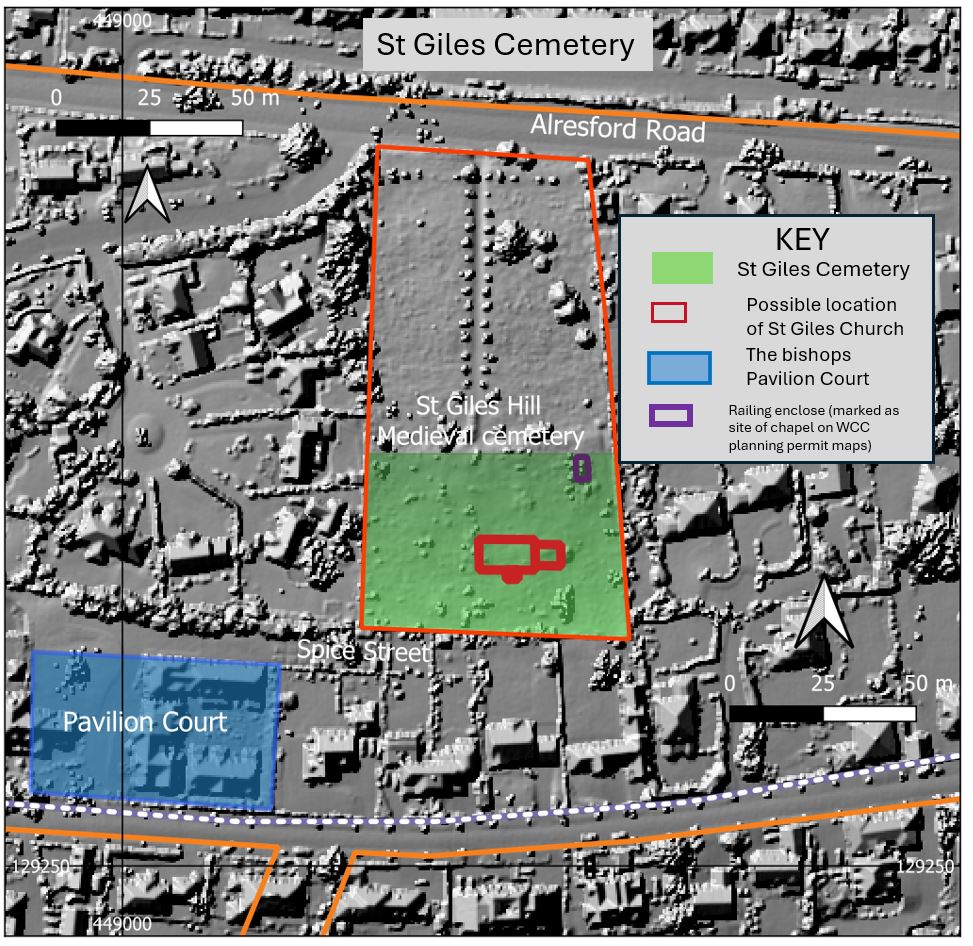

Map of St Giles Hill Fair

The nucleus of the fair was located on the brow of St Gile Hill. There were ditches and possible medieval walls around the fair which included a large space on the northern side of the now Alresford road. This was known as Vila Nova - ‘new town’ the bishop's new area that extended down to Winnall. This area may have been use for grazing or tethering at fair time. There were three tollgate entrances to this area. At times the extent of the fair extended beyond these boundaries down the slope towards the city and maybe up towards Magdalen Hill Down.

The opening and operation of the Fair

The West Gate of Winchester

The opening of the fair had a substantial effect on the municipal life of Winchester and the area around it for the following days. On the eve of St. Giles, the officers of the bishop rode out from Wolvesey Palace and entered the city at Kingsgate, where the mayor, bailiffs, and citizens met them and handed over the city keys to the gate. A proclamation that the fair had begun was made. 'Let no merchant or other for these sixteen days within a circuit (radius) of seven leagues (35km) round the fair, sell, buy or set out for sale any merchandise in any place other than the fair under penalty of forfeiture of goods to the Bishop. This ceremony was repeated at each gate where the keys were received. The officials also took custody of the great 'trona' or weighing beam. The bishop's officials and town officials then rode out of Winchester in procession with the town officials and the weighing beam, through the East Gate to the Pavilion Hall on St. Giles' Hill to set up court. From this point, the entire life of the city and the area around (almost to the outskirts of Southampton) was controlled from the Pavilion Court.

During the period when the fair was extended for 16 days, it was divided into two phases. The first from the vigil of St Giles to the Virgin Mary (8th September) was the time when the merchants were supposed to bring in their goods and pay toll. This was followed by 8 days when selling could commence. If merchants wished to bring in goods during this phase they had to pay a fine in addition to the toll. Over the 3 or 4 days following the 16th day the bishop's men went around the fair moving the merchants on.

The Pavionin Court

The Pavilion Court was the bishop’s court-house at St Giles's fair. The court regulated and settled disputes between merchants during the Fair's running and tolls and collected fines for the bishop. The Pavilion was first recorded circa 1200. In the 13th and 4th C, the bishop’s administration of the fair was highly complex and employed a considerable staff, some of whom probably lived and worked at the Pavilion. These included a justiciar, a chamberlain, a marshal, a gatekeeper, and a group of eight or more armed sergeants, who guarded the Pavilion. The Pavilion and the church of St Giles were the nucleus of the fair. They are two of the few fixed points of the fair that we know.

St Giles Hill Cemetery and the Bishops Pavilion court

By the 16th century the Pavilion Court had come to be known as Palme Court. This was the origin of the name of a house that later stood on the site of the court, known as Palm Hall. The name was later changed to Milesdown.

The layout of the fair

Although there is no specific description of the layout of the fair it is known that the streets were arranged in a grid pattern. Some of the streets were probably very similar in appearance to those within the medieval walled city of Winchester with shops upper rooms and cellars. Most of the properties were probably only occupied during the fair for short periods each year. Others along the more prominent streets may have inhabited throughout the year. It is not known when the grid of streets can into being. Early buildings of the fair were probably constructed from wood. But stone is mentioned from about 1287.

Merchants specialising in particular goods occupied specific locations and streets at the fair. Many streets housed wool traders (particularly in the 13th century) because this was one of the main products of the bishop's land. Cloth imported from Flanders, perhaps in particular from Ypres and Douai, was probably the principal commodity brought from overseas. Canvas and linen were also sold in quantity, and it is possible that some of the canvas was imported from France. Documents show that St. Giles’s fair was a major livestock market, where oxen, cart horses, sumpter horses, and palfreys were bought and sold. Leather goods, particularly saddles, bridles, boots, and gloves were important commerce as were Furs. After wool, cloth, and livestock, the most significant trade was probably in spices and gold. Traders from Dinant imported metal vessels may have made up a larger share of the trade than formerly.

At its height in 1292 there are estimated to have been 750 properties at the fair. Decreasing to perhaps 40 in 1390.

Who attended the fair

Both native and foreign merchants attended the fair each September and set out their goods for sale in the booths on the hill.

Many of the English traders came from London, and many were the goldsmiths of London selling their jewellery. Clothiers came from York, Beverley, and Leicester. The northern cities may also have sent wool and hides. Hampshire and the neighbouring counties probably supplied the bulk of the hides as well as horses and other livestock. Wool was sent from the Cotswolds and Hereford. People from the west country probably brought tin and lead. In the 14th century, they were the main merchants to come from a distance. In the middle of the 13th century the Irish visited the fair.

The foreign travellers included merchants from Spanish, Provençal Gascons, people from Ypres, Ghent, Bruges, Louvain, Dinant, Ardenburg, Douay and Dam, Brabanters, French and Normans. Spices and silks of the East were probably sold by Italians. Woad came from Toulouse, the bulk of the wine from Gascony. Other items include iron from Spain and the fine textile stuffs, madder and brassware from the Low Countries and the Rhineland. Most overseas merchants probably came from Flanders and neighbouring areas. Traders from Dinant imported metal vessels. There were also traders from the south-west and from Ireland who shipped through Southampton.

Provenance of merchants at the fair

The grid of streets was organised in an east-west, north-south arrangement. A flavour of the setup follows. The origin of many of the merchants is reflected in the street names given in the fairs accounts documents. Wool was sold in Wool Street which probably ran E-W and also in Hereford Street (also E to W) and Exeter Street. Parmenters' Row which also runs E to W housed shops of the London burellers. Goldsmiths' Row probably lay to the N. of the bishop's Pavilion. Skinners' Row was north of Parmenters' Row and ran N-S. French Street also ran N-S. Cornish Street and Oxford Street were parallel to one another. Old Cloth Street probably ran E-W as did Haberdashers' Row. Saddlers' Row where boots were sold probably also ran from E-W. Spicers' Street ran E-W and was parallel to and to the N. of High Street. Bristol Sreet was parallel to Spicer Street and to the north of Goldsmiths' How which probably ran from N- S and was at right angles to Spanish Street which was near Parmenters’ Row. Mercers’ Row ran from E-W and probably lay near the church of St. Giles. Cutlers' Row ran N-S. Potters’ Row, where earthenware and metal vessels may have been sold.

Decline of the fair

The fair probably reached its height by about 1240 when it drew large numbers of international merchants. It was one of a cycle of major English fairs which included those of St. Ives beginning at Easter, Boston beginning on 17 June, and Northampton beginning on 1 November. Merchants probably moved from one to the next. Following its peak multiple local and international disruptions had a detrimental effect on the fair. Events that disrupted the wool trade had a particularly severe effect on attendance of the fair.