St Giles Hill Graveyard memorials

A summary

St Giles Hill Graveyard has a variety of memorials the date of which stretch back to 1694. There are seven official Commonwealth war graves all from WW1. Many family gravestones also remember their family members lost overseas in WW1. There are several historically interesting memorials, such as the Lucas family "Titanic" memorial, memorials to important people from the local community, and 18thC graves with stunning artwork. What you will see depends on which part of the graveyard you are in as the original medieval graveyard was extended in 1870. The map below shows the location of the medieval area (pink - sections A to D) and the Victorian extension (green - sections E to J).

The type of memorial ranges from headstones, footstones, box tombs, stone and wooden crosses, stone scrolls, and a variety of less common grave markers. Headstones are the earliest form of marker in this graveyard. The oldest headstone is more than 300 years old. See Medieval Graveyard page.

The inscriptions of some stone monuments have been worn away by the elements and lost forever. The names of many people buried in the simpler graves are now also lost because wooden crosses that marked the graves have since disintegrated.

As with most church graveyards, the graves are laid out east-west. Typically, the head is at the western end of the grave so that it is facing the risen Christ on Judgement Day. In St Giles Hill Graveyard headstones appear the be laid out facing both east and west. We don’t know why.

The tradition of burial with the head facing east-west was very strong until the rural cemetery movement, which began in the 1830's and diminished the role of church cemeteries. Private companies opened cemeteries that were more park-like with hills and attractive settings, where the headstones were set to fit the contour of the terrain rather than adhering to an east-west orientation.

In St Giles Hill Graveyard even the 18th-century headstones face both ways. A Minister of the church was sometimes buried with his head at the eastern end of his grave, so he’d be facing his flock at the time of Resurrection.

There is one example of a back-to-back burial in St Giles Hill Graveyard that belongs to Herbert Maundrell an Archdeacon who has served in Japan and his wife Alice. Alice is buried in the customary way with her head facing east whereas he is buried with his head facing west.

Headstone Archdeacon Maundrell - looking east

Headstone Alice Maundrell - looking west

Headstones dominate in the medieval part of the graveyard. They include single and double headstones. Massive box tombs were common in the late 18th and early 19th C and can only be found in the medieval part. Stone surrounds begin to appear in the mid 19th C.

Example of an early 19th-century box tomb

The conventional layout with double-headed is for the wife to be to the left and the husband to the right as in the example below.

Late 18th and early 19th century headstone artwork abounded with sculls, cross-bones, cherubs, or angles with wings and trumpets. The skull and Cross Bones on a headstone in the older part of the graveyard are from this period. This motif was like a Memento Mori, a reminder of our mortality and a reminding the onlooker that you too will die one day. The oldest burials known in the graveyard, found on higher ground at the south end, have single and double headstones. Some of the single gravestones are richly ornate with cherubs, sculls, and trumpets.

Early 19th-century headstone - No 265 Sarah Ann Kellow 1825

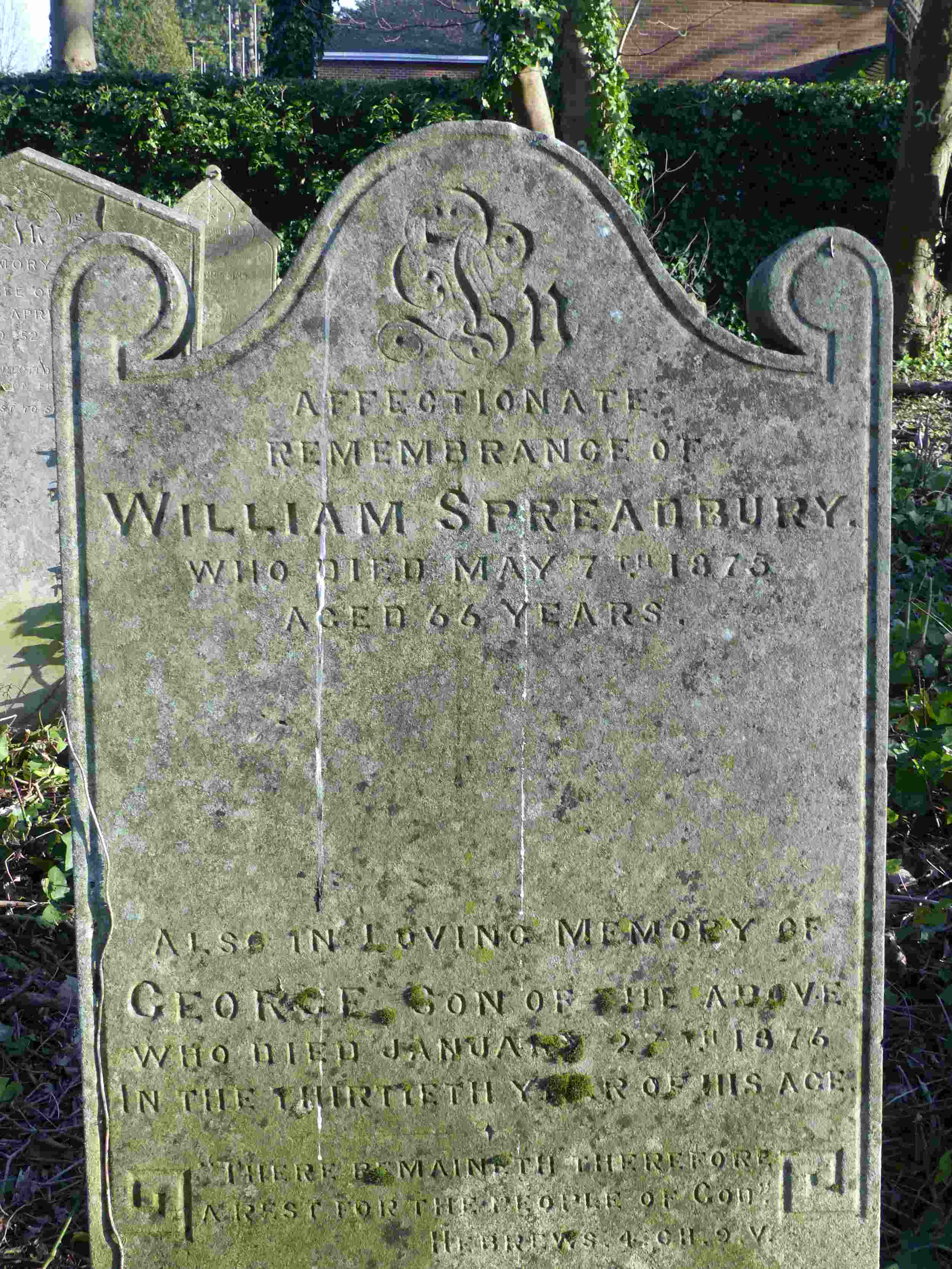

Later in the 19th century, headstones became bigger, more solid, and bore more detailed inscriptions and the first stone surrounds started to be used on burial plots. There are only 4 stone surrounds in the medieval part of the graveyard. Headstones were decorated with a new fashion of symbolic images representing faith, glory, hope, or the deceased earthy occupation. Symbols on headstones include various types of handshakes that symbolised the last farewell.

Example of handshake

In the 20th C, although limestone or wood was still widely used as a gravestone material, more resistant granite became popular.

White granite celtic cross

In the mid-20th century, wooden crosses became common, probably as an option for the not so well off. At one time there were many wooden crosses in this graveyard. Particularly in the lower section close to the Alresford Road. Only about 5 remain. One of the wooden crosses, marking the burial of a 10-year-old boy Charles Ronald Clay who died in 1940, is still tended by relatives. It is thought that he died from a bee sting and was buried with his granny. Unfortunately, they are prone to rot and only 6 or 7 remain, and only 2 of those record the owner's names.

Example of Scroll

Wooden cross of Ronald Clay

Late usage of the graveyard:

After WW2 usage of the graveyard appears to have declined, although it is not easy to say because there are many unmarked plots. It is likely that these plots were originally marked with wooden crosses now gone. Unfortunately, the cemetery records have been lost. There were several burials in the 60's and 70's followed by inactivity. The latest burials appear to have taken place in 1973. One of these graves, located behind the stone enclosing wall, close to the Alresford road belongs to Flossi Jane Hughs. The stone surround can be found just inside the main gate ofn the left.